Why Are Kids So Hungry After School?

Oct, 30 2025

Oct, 30 2025

After-School Hunger Gap Calculator

School day ends at 3:00 PM by default. Your child's hunger timing depends on:

- Time since last meal

- Physical activity level

- Protein/fat content in lunch

Key Insight: Lunches low in protein/fats cause blood sugar crashes 1-2 hours sooner.

Estimated Hunger Time

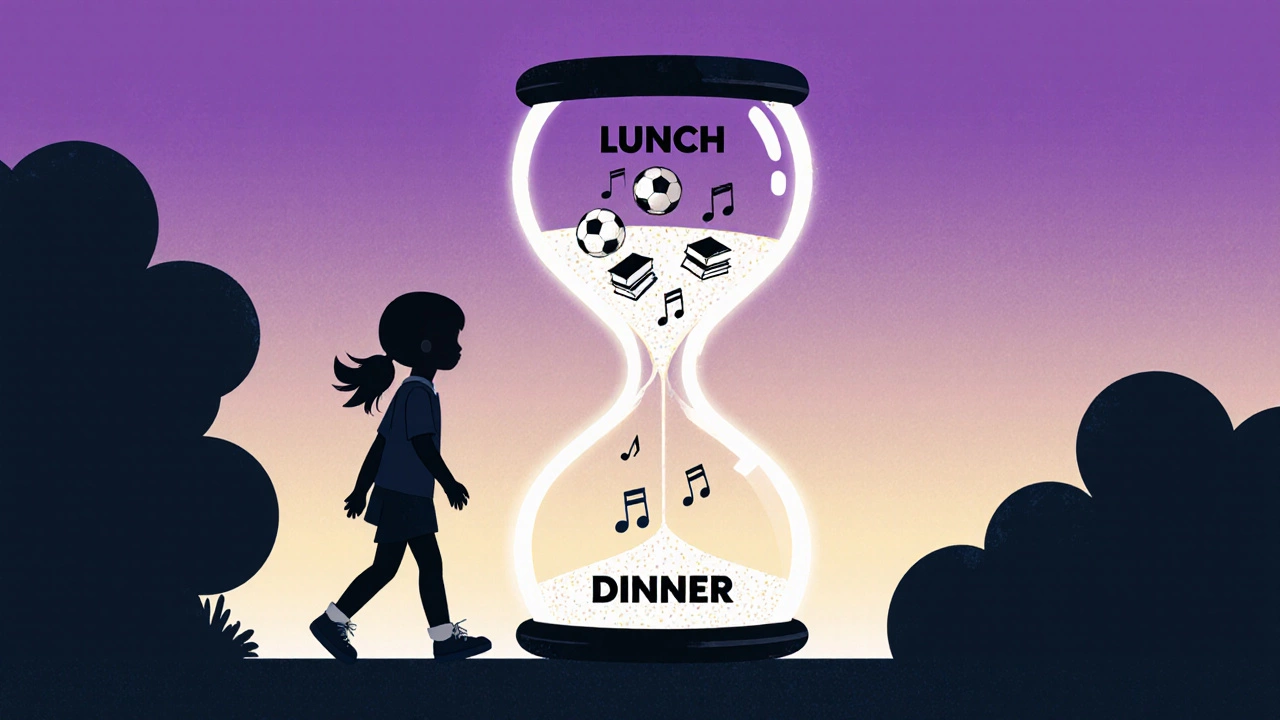

Every afternoon, around 3:30 p.m., the school gates open and kids flood out-tired, buzzing with energy, and often, ravenous. You’ve seen it: the way they dive into their backpacks for a granola bar, the way they beg for snacks the second they step through the door. It’s not just being picky. It’s not just a phase. There’s a real reason kids are so hungry after school-and it’s tied to more than just growing bodies.

The Science Behind After-School Hunger

Children burn energy fast. A typical school day isn’t just sitting at a desk. It’s walking between classes, standing in line, playing during recess, even fidgeting in their seats. Studies show that kids aged 6 to 12 use up to 1,500 to 2,000 calories a day just for basic activity. Breakfast, if they ate it at all, was likely four to five hours ago. Lunch? That was probably at noon. By 3 p.m., their blood sugar has dropped, their energy reserves are tapped, and their bodies are screaming for fuel.

But it’s not just about time. Many kids don’t get enough at lunch. School meals are designed to meet federal nutrition guidelines, but those guidelines don’t always match what a growing child actually needs. A sandwich with a side of carrots might be ‘balanced’ on paper, but if it’s low in protein and healthy fats, it won’t keep them full for long. One 2023 study from the University of Queensland found that 42% of primary school children in Australia reported feeling hungry again within two hours of lunch, even when they ate the full school meal.

After-School Clubs Make It Worse

Here’s the twist: the very programs meant to help kids-after-school clubs, sports, music, tutoring-often make the hunger worse. Kids stay an extra two or three hours past the end of the school day. They’re running drills, practicing piano, building robots, or hiking through a nature trail. All that activity burns even more calories. And what do they have to eat? Nothing.

Most after-school programs don’t provide snacks. Even if they do, they’re often inconsistent. A soccer club might hand out fruit on Tuesdays but forget on Thursdays. A homework club might say, ‘Bring your own snack,’ but not every family can afford to pack one every day. For kids who rely on school meals for most of their daily nutrition, the gap between lunch and dinner can stretch to eight or nine hours.

It’s Not Just About Food-It’s About Access

Some families can’t afford to feed their kids snacks every day. In Brisbane, one in five children lives in a household that struggles to put enough food on the table. That doesn’t mean they’re homeless or starving-it means they’re choosing between paying the electricity bill and buying apples. Or they’re working two jobs and don’t have time to pack snacks. Or they’re living in a food desert where the nearest fresh produce store is a 40-minute bus ride away.

And when kids are hungry, it shows. They can’t focus in homework club. They get irritable during choir practice. They zone out during robotics sessions. Teachers notice. Coaches notice. But no one always connects the dots to hunger.

What’s Being Done-And What’s Missing

Some schools and community groups are stepping up. In Logan, a primary school started a ‘Snack & Learn’ program where kids grab a granola bar and a piece of fruit before heading to their after-school activity. In Redcliffe, a local church partners with the high school to run a Friday snack cart-free, no questions asked. These aren’t fancy solutions. They’re simple. But they’re rare.

Most after-school programs still treat snacks as an optional extra, not a core part of the service. Even when funding is available, it often goes to equipment, uniforms, or software-not food. There’s no national standard for snack provision in after-school care. Unlike school meals, which are federally funded, after-school snacks rely on goodwill, grants, or parent donations. That’s not reliable. That’s not fair.

What Parents and Communities Can Do

You don’t need to run a nonprofit to help. Here’s what actually works:

- Ask your school or club: ‘Do you have a snack policy?’ If not, suggest one. Even a simple rule like ‘All clubs provide one healthy snack daily’ makes a difference.

- Start a snack box. Keep a basket of non-perishable snacks-granola bars, dried fruit, peanut butter packets-in the classroom or club room. Ask parents to donate one item a week. Rotate it. No one has to give much, but together, it adds up.

- Push for funding. Local councils often have grants for youth programs. Apply for one to cover snack costs. Frame it as ‘improving learning outcomes’-hungry kids learn slower. That’s not opinion. That’s science.

- Normalize asking. If your child says they’re hungry, don’t assume they’re just being dramatic. Ask if they ate lunch. Ask if they had a snack after school. If they say no, it’s not a failure-it’s a signal.

The Bigger Picture

Hunger after school isn’t a minor inconvenience. It’s a barrier to learning, to development, to childhood itself. Kids who are constantly hungry are more likely to fall behind academically, struggle with behavior, and feel ashamed. They learn that their needs don’t matter. That’s not just bad policy-it’s bad for everyone.

When we provide snacks after school, we’re not just feeding bodies. We’re saying: you matter. You’re worth the time. You’re worth the cost. You’re worth the effort.

It doesn’t take a lot to fix this. Just a few granola bars. A few minutes of planning. A few adults who decide it’s time to stop ignoring the obvious.

Why do kids get so hungry after school even if they ate lunch?

Kids burn through energy fast-especially with physical activity, movement between classes, and growing bodies. Lunch is often served at noon, and by 3 p.m., it’s been five hours since their last meal. Many school lunches also lack enough protein or healthy fats to keep them full, so their blood sugar drops quickly, making them feel hungry again.

Are after-school clubs making hunger worse?

Yes. After-school clubs extend the day by two to three hours, often with physical or mental activity that burns extra calories. But most programs don’t offer snacks. Kids go from lunch straight into soccer, robotics, or tutoring with nothing to eat-turning normal hunger into real energy depletion.

Is this a problem only for low-income families?

No. While low-income families face greater challenges, hunger after school affects kids across all income levels. Even middle-class families might forget to pack snacks, or kids might leave their lunch at home. The issue is systemic: most after-school programs don’t plan for snacks, regardless of family income.

What kind of snacks work best after school?

Snacks that combine protein, fiber, and healthy fats last the longest. Think: apple with peanut butter, cheese sticks with whole-grain crackers, yogurt with granola, hard-boiled eggs, or trail mix. Avoid sugary snacks-they give a quick boost but crash fast, leaving kids hungrier than before.

Can schools legally provide snacks after school?

Yes. While school meal programs are federally funded, snacks after school aren’t covered the same way. But schools can use community grants, parent donations, or partnerships with local food banks to provide snacks. Many do-it’s just not yet standard practice. No law stops them.

What if my child says they’re not hungry after school?

Some kids don’t recognize hunger cues, especially if they’ve been used to going without. Others might be too tired or overwhelmed to speak up. Watch for signs: irritability, zoning out, headaches, or sudden cravings for sugary foods. These can all signal low blood sugar. Offer a snack anyway-it’s better to be safe than sorry.