What Are the Disadvantages of a CIO in a Charitable Trust?

Feb, 20 2026

Feb, 20 2026

Charitable Trust Investment Impact Calculator

Input Your Trust's Data

How This Works

Enter your trust's current endowment and annual budget to see how different investment returns affect your program's sustainability. The calculator shows both the minimum return needed to maintain current operations and the impact of higher returns on expanded services.

Key factors: A 5% return on $10M provides $500,000 annually. A 2% return on the same endowment provides only $200,000 - potentially forcing program cuts.

Impact Analysis

Risk Level:

When people think about charitable trusts, they often picture volunteers handing out food, fundraisers, or kids getting school supplies. But behind the scenes, there’s a role that’s critical - and often misunderstood - the Chief Investment Officer, or CIO. In a charitable trust, the CIO manages the money that keeps the charity running. They invest donations, grow the endowment, and make sure funds are available for programs years down the line. Sounds important? It is. But it’s not without serious downsides.

The CIO Isn’t Just a Fund Manager

In a charitable trust, the CIO doesn’t work for shareholders. They work for a mission. That means every investment decision has to balance two things: making money and staying true to the charity’s values. If the trust supports environmental causes, should they invest in fossil fuel companies just because they’re profitable? Many CIOs say yes - and get criticized. Others say no - and risk running out of money. That tension is constant, and it’s one of the biggest disadvantages of the role.

There’s no playbook. Unlike a corporate CFO, the CIO in a charity can’t just follow industry benchmarks. They’re expected to be ethical investors, financial experts, and mission guardians - all at once. And if they make a mistake? The public doesn’t blame the board. They blame the charity.

Pressure to Perform, With No Room for Error

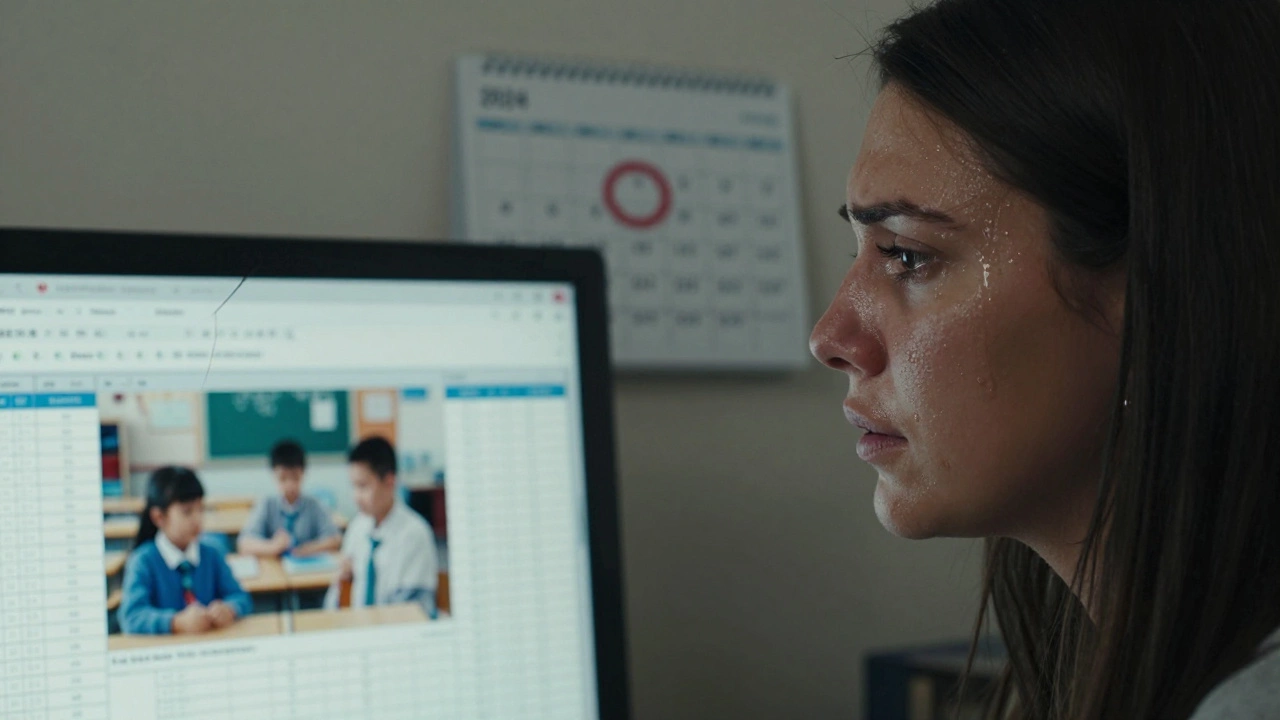

Charitable trusts rely on investment returns to fund their work. If the market drops, and the CIO didn’t hedge properly, programs get cut. Staff get laid off. Kids lose access to tutoring. Volunteers notice. Donors notice. And then? The headlines start.

A 2023 report from the Charities Aid Foundation showed that 68% of UK-based charitable trusts saw a drop in spending power after a single year of poor investment performance. In Australia, a small trust in Brisbane lost $1.2 million in 2024 when their CIO bet heavily on renewable energy stocks - a move that seemed aligned with their mission, but crashed when policy changes hit the sector. The trust had to pause its youth outreach program for nine months.

There’s no safety net. Corporations can borrow, raise capital, or cut costs. Charities can’t. Their CIO is the only one holding the financial lifeline. One bad year, one wrong bet - and the whole operation can unravel.

Lack of Expertise and Resources

Most charitable trusts don’t have the budget to hire a top-tier CIO. They often pick someone from the finance department who’s good with spreadsheets - not someone with decades of institutional investing experience. The result? Underqualified leaders making high-stakes decisions with minimal support.

A 2025 survey of 120 Australian charitable trusts found that 71% of CIOs had no formal investment training. Many were former accountants, teachers, or even retired nurses. They were chosen because they were trustworthy - not because they knew how to manage a $10 million portfolio.

And it’s not just about skill. Most trusts don’t have access to the tools big institutions use: real-time risk modeling, hedge fund access, proprietary data analytics. They’re using free online platforms and basic spreadsheets. That’s like asking a volunteer to fly a jetliner with a paper map.

Conflicts of Interest and Hidden Biases

It sounds simple: invest wisely, support the mission. But in practice, it’s messy. A CIO who believes deeply in climate justice might avoid all oil companies - even if they’re the most stable assets. A CIO who’s personally invested in tech startups might tilt the portfolio toward those, even if they’re risky.

And it’s not always intentional. Unconscious bias plays a role too. One trust in Sydney avoided investing in Indigenous-owned businesses because their CIO didn’t understand the financial models - not because they were opposed, but because they didn’t know how to evaluate them. That’s a blind spot. And blind spots cost money.

There’s also pressure from donors. Some donors say, “Only invest in companies that align with our values.” Others say, “Just make the highest return possible.” The CIO gets caught in the middle. They can’t please everyone. And trying to try ends up pleasing no one.

Transparency vs. Strategy

Charities are expected to be open. Donors want to know where their money goes. So the CIO has to explain complex investment decisions in plain language. “We allocated 15% to emerging market bonds because they offer higher yield with moderate risk.” That sounds fine on paper. But when a donor reads it? They think, “Why are we investing in countries with unstable governments?”

There’s no good way to simplify this. The more detail you give, the more confusion you create. The less you say, the more people suspect you’re hiding something. That’s why many CIOs end up saying nothing at all - which makes donors feel ignored, and that’s just as damaging as a bad investment.

The Emotional Toll

Most people don’t realize how heavy this job is. The CIO isn’t just managing money. They’re managing guilt.

Every dollar they don’t invest in a high-return fund is a dollar that could have fed more kids. Every dollar they invest in something risky is a dollar that could have been lost. They carry the weight of every child who might go without, every family who might lose support.

One CIO in Adelaide told a reporter in 2024 that she cried after her first year-end report. The portfolio had grown by 4.7% - a solid result. But she said, “I kept thinking: what if we’d made 6%? Could we have hired another social worker? Could we have kept the after-school program open?”

There’s no HR department for CIOs. No counseling. No breaks. Just a spreadsheet, a mission, and a conscience.

What Can Be Done?

It’s not all doom. Some trusts are fixing this. A few are hiring external investment advisors - not full-time CIOs, but consultants who work on retainer. Others are forming alliances: three small trusts pool their funds and hire one expert CIO to manage them all.

Some are training their CIOs. One trust in Melbourne runs a yearly workshop with university finance professors. Another created a mentorship program with retired institutional investors.

And some are changing their expectations. Instead of demanding 7% annual returns, they’re accepting 3% - and using it as a chance to focus on ethical alignment over profit. It’s not glamorous. But it’s sustainable.

The truth? The CIO role in a charitable trust is one of the hardest jobs in the nonprofit world. It’s not about being rich. It’s about being responsible. And sometimes, being responsible is the hardest thing of all.